Light and logic strengthen Sweden’s defence capability

When Sweden’s photonics sector recently gathered in Kista for Optics & Photonics in Sweden (OPS), one theme dominated – defence. The conference demonstrated how light-based technology is rapidly becoming a cornerstone of Europe’s security capability.

Behind every drone, every satellite and every secure communication link, light is now becoming a strategic necessity. But what makes photonics so vital to modern defence, and what positions Sweden as a strong contributor?

The photonic advantage in modern defence

Photonics – the science of how light can be controlled and applied – makes it possible to create systems that are faster and more efficient than traditional electronics. When combined with semiconductor technology, information can be transmitted more quickly, with lower energy consumption and higher precision.

Concrete applications include infrared sensors and LiDAR systems that detect drones and missiles long before they appear on conventional radar. Optical communication links enable secure, interference-free data transfer, and in the future, quantum photonics will open the door to unbreakable encryption and even more advanced detection systems.

A Swedish ecosystem for innovation

In Sweden, a complete photonics ecosystem has emerged, bringing together research, innovative startups and international industry. Each category contributes to the nation’s technological sovereignty and defence readiness:

Sensor and Imaging Technology

- IRnova – Develops advanced infrared detectors extending the range and precision of surveillance and targeting systems across air, land and maritime domains.

- Teledyne FLIR – Delivers multispectral and thermal imaging systems for drone detection, target tracking and battlefield monitoring, enhancing situational awareness.

Semiconductor and photonic integration

- Mycronic – Provides world-leading photomask writers and die-bonding equipment used in the manufacturing of next-generation photonic and semiconductor chips, ensuring secure and traceable European production capacity.

- Silex Microsystems – Operates one of the world’s most advanced MEMS foundries, producing miniaturised sensors and actuators critical for navigation, guidance and environmental sensing in modern defence systems.

Laser and optical systems

- Lumibird Photonics Sweden – Supplies high-performance laser rangefinders and designators for naval, airborne and ground applications, contributing to precision targeting and autonomous systems.

Together, these companies, along with coordinative initiatives like Semiconductor Arena in Kista Science City, form the basis of a national value chain where research becomes production – and production becomes operational capability.

From policy to capability

Transforming innovation into defence capability requires coordination. Photonics, as the optical backbone of next-generation chips, represents the intersection where Sweden’s strengths in defence innovation meet Europe’s semiconductor ambitions.

“Over the past year, we’ve noticed a clear increase in openness and curiosity from both defence organisations and their industrial partners. It’s not just about scouting new technology anymore – it’s about understanding what Swedish deep-tech companies can bring to the next generation of systems,” says Peter Tiberg, Chief Product & Commercial Officer at Polar Light Technologies, a Swedish startup at the forefront of MicroLED development. “For us, this means focusing on building trust through transparency, reliable delivery, and long-term commitment rather than quick pivots.”

Within the framework of the EU Chips Act and a broader ambition for strategic autonomy, Sweden contributes its expertise to the shared defence goals of the EU and NATO. Standardisation and cooperation strengthen interoperability, allowing allied systems to share both materiel and data.

Sweden’s Minister for Defence, Pål Jonsson, has emphasised the strategic link between semiconductors and national security. At the core of this lies Europe’s common need for technological sovereignty – and to secure knowledge and production capacity within the Union’s borders.

The time is now

A global race is underway, as nations invest heavily in semiconductors and emerging technologies such as photonics. Sweden is uniquely positioned, with expertise across the entire value chain – from laboratories and test facilities to companies that have advanced optical science for decades.

“Right now, enormous amounts of money are being poured into the market,” says Raoul Stubbe, Deep Tech Business Coach and Co-founder at Sting. “It creates opportunities for new actors to take their place. But once the funds are locked into long-term projects in Sweden and NATO, the window for new initiatives will close.”

The Swedish ecosystem already has all the pieces in place to succeed in combining light (photonics) with logic (semiconductors) and defence. The next step is increased coordination between actors at all levels throughout the chain, from research and production, and ultimately military capability. To secure a strong position, we need the determination to act together – before others do.

Do you want to get involved? Reach out to hanna.eldh@kista.com

–

Semiconductor Arena is co-funded by the European Union and Region Stockholm, and is run by Kista Science City, KTH, RISE and Sting.

Setting the agenda: Semiconductor Arena launches in Kista

Sweden’s semiconductor ecosystem now has a shared platform in Kista. Semiconductor Arena brings startups, industry and researchers together to develop skills, support companies and strengthen Sweden’s role in Europe’s semiconductor landscape.

The race for semiconductor sovereignty

Semiconductors power almost every modern system — from transport and energy to communication and health. As demand grows, Europe is investing heavily to reduce its dependence on external suppliers and secure local capacity.

Sweden has key strengths to build on: world-class research, advanced infrastructure and a strong base of specialist companies driving innovation. The challenge is to turn that technical know-how into industrial capacity, and to ensure Sweden plays a clearer role in Europe’s semiconductor future.

Semiconductor Arena

The launch of Semiconductor Arena marks a new phase for Sweden’s chip sector, bringing startups, industry and researchers closer together.

The Arena, developed by Kista Science City, KTH, RISE and Sting, is a neutral meeting ground where ideas can move beyond individual organisations and into shared initiatives. Here, companies and researchers from different fields can test ideas, share expertise and move projects forward together. By connecting strengths across the ecosystem, the Arena shortens the path from research to industrial impact and builds the networks and visibility that help companies grow.

The launch in Kista highlighted three priorities that will shape this work: attracting and training more talent, enabling companies to scale in Sweden and connecting regional strengths with both Sweden’s national strategy and Europe’s semiconductor agenda.

Building Sweden’s talent pipeline

The skills gap is one of the semiconductor sector’s most pressing challenges. Established companies point to an urgent need for more engineers and stronger incentives to enter the field.

“One concrete action is to reach engineers earlier in their academic journey so they see Sweden — and Stockholm in particular — as a strong hub with real career paths,” says Niklas Svedin, CTO and co-founder of Silex Microsystems, one of Sweden’s leading semiconductor companies.

Startups share the concern but see a different missing link: the difficulty of giving students and researchers clear entry points into real projects. “The most urgent need is structured competence initiatives that make it easier for students and researchers to engage with industry,” adds Louise Ribrant, VP of Business Development at Myvox, a startup specialising in MEMS ultrasound technology.

Semiconductor Arena is set up to address these needs, from early visibility to practical entry points. In the months ahead, the Arena will roll out initiatives to connect students with companies — starting with a thesis fair. Alongside this, the Electrum Lab will be made more accessible as a shared national resource, giving innovators hands-on access to state-of-the-art equipment.

Beyond engineers, companies also stress the importance of technicians and vocational roles to support large-scale production. To meet this need, the Arena will introduce new vocational training offers, preparing more people for hands-on roles in production.

Creating conditions for growth

Alongside the need for talent, another challenge for Swedish semiconductor companies lies in scaling their business. Moving from a small team to an established company is difficult. Development cycles are long and capital needs are high — and with limited financing options in Sweden, promising startups are too often acquired abroad, taking both competence and value with them.

Semiconductor Arena lowers these barriers by helping companies access infrastructure, connect with investors and build stronger ties across industry and academia.

One example of this approach is Sting’s Test Drive programme, which now includes a dedicated track within Semiconductor Arena to support researchers and startups. Test Drive is a short, workshop-based format that helps teams explore whether an idea can become a company. Concepts are tested with investors and mentors, giving them early clarity, confidence and networks.

“Being part of Semiconductor Arena connects us to a stronger innovation ecosystem at a critical time for both Sweden and Europe,” says Louise Ribrant of Myvox. “The Arena is a way to access competence, infrastructure and partners that can help accelerate development and commercialisation.”

Turning regional strengths into national influence

Sweden’s semiconductor sector has expanded quickly in recent years. Strong research environments, new startups and regional hubs are all contributing to a broader and more dynamic ecosystem. Yet much of this growth has developed in parallel, with initiatives often moving forward without alignment. Without stronger coordination, these efforts risk fragmenting — weakening Sweden’s ability to influence Europe’s semiconductor agenda and build long-term resilience.

Semiconductor Arena makes coordination day-to-day practice. Firmly rooted in Stockholm’s ecosystem, it gives local companies and researchers greater visibility by mapping actors and capabilities, showing who does what and where. By highlighting Stockholm’s semiconductor strengths, the Arena also makes it clearer what the ecosystem can contribute to Sweden’s national strategy and Europe’s semiconductor agenda.

Ultimately, coordination is about positioning — ensuring Sweden is not just part of Europe’s semiconductor agenda but able to shape it. As Niklas Svedin notes, self-sufficiency has become a central issue in Europe, making it urgent to put the semiconductor industry firmly on Sweden’s agenda. “The Arena helps connect industry, academia and policymakers — creating a stronger collective voice,” he says.

Looking ahead

Semiconductor Arena has brought Sweden’s chip sector into closer dialogue, turning collaboration into a working method rather than an exception. The next phase will build on this momentum: translating shared priorities into concrete initiatives — from clearer student pathways to new international connections.

The direction will be set by the ecosystem itself. As new needs emerge — whether in training, infrastructure or policy dialogue — the Arena provides a place to meet them collectively. Anchored in Stockholm and connected to national and EU strategies, it offers Sweden a stronger platform to act collectively in the global chip race.

Do you want to get involved? Reach out to hanna.eldh@kista.com

—

Semiconductor Arena is co-funded by the European Union and Region Stockholm and is run by Kista Science City, KTH, RISE and Sting.

New paths for Swedish research: Test Drive shows the way

Sweden has a strong tradition of research. This is reflected in the quality of its universities and institutes, and it underpins the country’s reputation for innovation. Yet many ideas still stall in the early stages, left on the shelf before they can be developed into companies. The reasons are rarely about scientific quality; they are about what comes next.

Traditional models — from licensing agreements to longer incubator tracks — play an important role, but they don’t always reach researchers at the point where ideas are just beginning to take shape. Turning research into resilient businesses requires access to infrastructure, early business development and connections to industry. Without those building blocks, promising results risk getting stuck before they reach the market.

That is where new approaches are needed: formats that combine technical insight with business perspective and give early teams the confidence and networks to move forward. One example of such a format is Test Drive, a programme developed and run by our sister organization Sting. During spring 2026 Sting will launch a Test Drive track within Semiconductor Arena, a national initiative to strengthen Sweden’s semiconductor ecosystem.

A first look at entrepreneurship

Test Drive is a short, workshop-based programme that lets researchers and innovators explore what it would mean to take an idea further. Over four to five sessions, teams bring their own ideas — often two or three people working together — and examine them through a startup lens: could they attract funding, what role would each person need to take, and what would it mean in practice to move forward? The programme ends with a pitch event, giving participants direct feedback from investors.

“We want to give researchers and innovators a picture of what this journey could look like,” says Raoul Stubbe, business coach at Sting. “What does it mean for me personally? What steps would I need to take for this to happen? That’s often what flips a switch — when participants start to think, ‘maybe this really could become something.’ We want people to leave with the feeling that they want their ideas to come out and make a difference in the world.”

Lessons from Test Drive

For many participants, the biggest gain is seeing their work from a completely different angle — one that stands in contrast to the priorities of an academic career. Raoul explains:

“In academia, publication and tenure often come first. Building a company isn’t something you can do on the side. It requires full focus and a different way of thinking. The programme doesn’t make the decision for them, but it shows what’s required — and often gives people the confidence to decide whether to take the leap.”

The outcomes reflect that. Around half of those who complete Test Drive go on to start a company — a high rate compared to other formats. Others choose not to, but highlight the investor feedback, exposure and new perspective as valuable in themselves. “Even if the company doesn’t become what you first imagined, the experience opens up opportunities and a new way of looking at what’s possible. That’s one of the biggest wins,” Raoul says.

Valentin Dubois is CEO and co-founder of Dappler Labs, a startup developing quality-control technology for semiconductor manufacturing. He took part in a Test Drive programme in 2023 and recalls:

“What Test Drive really taught us was how important it is to package an invention into something that can be sold. For academics, that’s not obvious at all. They pushed us to think in terms of a minimum viable product, and also how to pitch a highly technical idea in a way people outside our niche could understand.”

Bridging research and business

Test Drive doesn’t only affect individual decisions. It also reshapes how researchers relate to investors, and vice versa. Many enter the programme with fixed views: researchers seeing investors as focused only on sales, and investors doubting whether researchers can actually lead companies. In Test Drive, those assumptions are tested. By working side by side, participants begin to see the value in each other’s expertise. “It’s about creating respect for the strengths each side brings,” Raoul explains.

The shift can also extend to how researchers view themselves. Raoul points to a particular type of academic who could play a bigger role in bridging this gap — what he calls the entrepreneurial scientist:

“These are individuals who match the rigour of traditional science with the curiosity and drive needed to build companies. Test Drive helps them recognise that identity in themselves — quite often for the first time. The programme shows that entrepreneurial ambition is not at odds with academic credibility, but a way to amplify the impact of their work.”

Moving forward

Test Drive is not a substitute for incubators, accelerators or licensing pathways. But it fills a crucial gap at the beginning of the journey, giving teams a structured first step that many existing models don’t provide. And it can be adapted. “These formats are portable,” Raoul Stubbe notes. “They can be tailored to new domains by adding the right pieces — access to infrastructure, industry mentors, a clear end goal. The principle is the same: help early teams see the path and take the first step.”

That adaptability has already been shown in dedicated tracks on health, energy and AI. The next step is deep tech and semiconductors. Within Semiconductor Arena, Sting will run a Test Drive track to help early-stage teams test and refine their ideas, and move them closer to implementation. With long development cycles and high capital needs, this is a field where early clarity is especially important for emerging teams.

Formats like Test Drive highlight a larger need in Sweden’s innovation system. The challenge is not producing strong research, but making sure it translates into companies and industries. Without that translation, the risk is not only missed growth, but dependency. As Raoul puts it: “This need is not new, but it is more urgent than ever today. Sweden measures up well against the US and China in research, but our weakness in transferring knowledge leaves us dependent on American and Chinese technology.”

Test Drive is one example of how that gap can be addressed. For Sweden, the task now is to make sure more such models take root — so that world-class ideas translate into the businesses, capabilities and resilience the country needs.

—

Semiconductor Arena is co-funded by the European Union and Region Stockholm, and is run by Kista Science City, KTH, RISE and Sting.

Semiconductor Arena

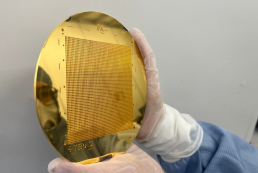

Image credit: TeraSi

Semiconductor Arena: A new platform for Sweden’s growing chip sector

The challenge

The global demand for semiconductors is rising fast. Across Europe, countries are investing to secure supply, build capacity, and reduce reliance on external producers. The goal: to strengthen Europe’s resilience in a technology that powers nearly all modern systems.

In Sweden, the need to boost domestic production and innovation efforts has become increasingly clear since the COVID-19 pandemic. When global supply chains were disrupted, Swedish companies felt the impact immediately. That period exposed structural gaps — from limited infrastructure and restricted access to production facilities, to weak links between industry, academia, and research. Looking ahead, the sector also faces a generational shift, making it critical to attract new talent and pass on expertise.

In Kista, targeted efforts are now being made to close these gaps and build a stronger, more connected semiconductor ecosystem.

Semiconductor Arena

Led by Kista Science City, KTH, RISE and STING, Semiconductor Arena is a new platform for advancing Sweden’s chip capabilities. By offering shared resources and meeting places for startups, researchers, and established companies alike, the Arena supports new innovation constellations and helps accelerate the path from research to commercialization.

A key ambition is to make Electrum Laboratory a more open and social hub for the industry. It will serve as a space for showcasing innovation, networking, and deep technical collaboration — a neutral platform for students, innovators, and leading players to meet, learn, and build together.

The Arena also supports broader outreach. That includes raising awareness of semiconductors and their societal relevance — and attracting new talent through matchmaking events, student fairs, and shared learning opportunities.

Planned activities for fall 2025 include:

- Thesis fair

- Startup coaching by Sting

- Onboarding early-stage companies to the Electrum lab environment

“Semiconductor Arena is about creating value today while laying the foundation for long-term competitiveness,” says Karin Bengtsson, CEO of Kista Science City. “The first step is to reach out to the semiconductor community to shape the platform together – by the industry, for the industry.”

A national centre

Kista’s position as a national semiconductor hub is central to this initiative. The area already hosts Sweden’s competence center for semiconductors and one of the EU’s pilot lines, operated by KTH through the EU Chips JU programme. Together, these assets create a unique environment of advanced infrastructure, world-class research, and deep industry expertise.

Building on these strengths, KTH is now expanding its activities at Electrum, including the launch of a new pilot line for power semiconductors. The goal is to accelerate production, support talent development, and strengthen Sweden’s role in building strategic capacity in the EU.

Do you want to get involved? Reach out to karin.bengtsson@kista.com